Money isn’t everything, but without it, science is hard. Really hard. Materials, people and legal fees are expensive!

According to a blog post by Maksym Sich on I F***king Love Science (originally The Conversation), “In 2012, the worldwide expenditure on scientific research and development was US$1.5 trillion, while an estimated 1.9m peer reviewed articles were published that year. This works out as a whopping US$790,000 per article.”

WOW! That’s more expensive that most houses, and this is just in one year. Now keep in mind that projects like space missions are hugely expensive and exaggerate this estimate a bit, but the figure is still recognizable as representative of the huge cost of science.

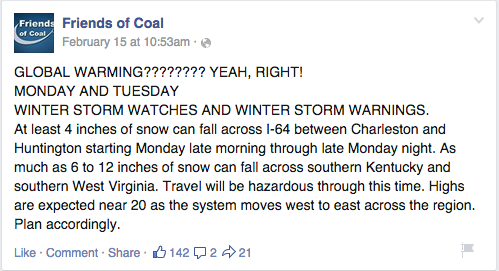

So how do we fund science research? Well, at best, we rely on government or universities. At worst, private companies fund the research. It’s an issue that has raised its fair amount of controversy recently. Remember Wei-Hock Soon? I blogged about him last month. Better known as Willie, he was a scientist associated with the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics who is best known for his claims that variations in the sun’s energy can largely explain global warming. This went against the more widely accepted belief (97% of scientists) that humans play a large role in global warming.

Soon’s beliefs weren’t really the problem, though. Although most scientists didn’t agree with him, arguing and testing theories is what science is all about. The real problem came from his fund  source: He accepted more than $1.2 million in money from the fossil-fuel industry over the last decade while failing to disclose that conflict of interest in most of his scientific papers.

source: He accepted more than $1.2 million in money from the fossil-fuel industry over the last decade while failing to disclose that conflict of interest in most of his scientific papers.

Whether Soon’s data is valid or not, not disclosing funding from an industry that happens to use his findings to their advantage presents quite a problem.

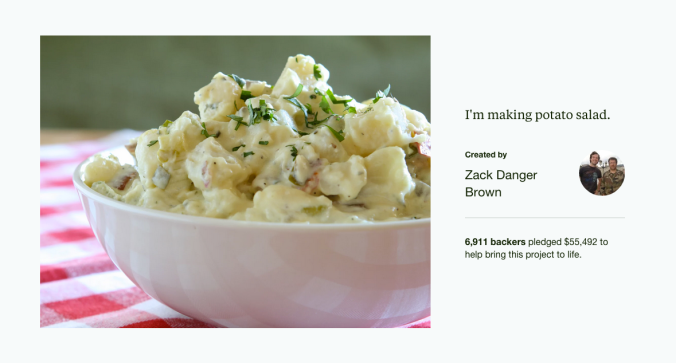

So what are other options? How around Crowdfunding? Its worked for video games, museums and even a charismatic gent who wanted to make some seriously stellar potato salad.

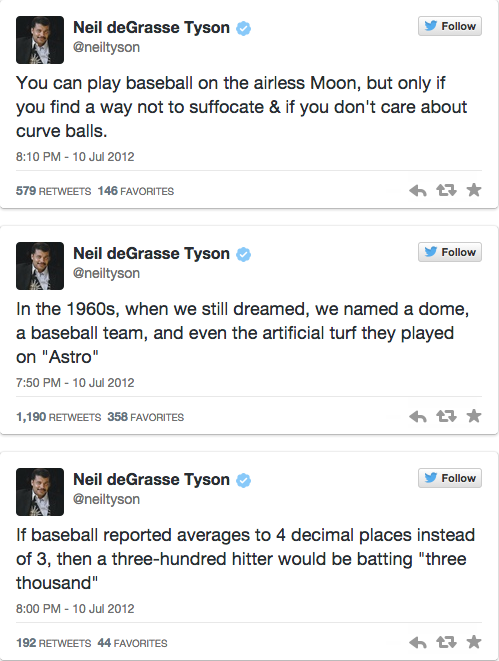

Science and technology has found a home in crowdfunding as well. The Pebble Watch, a modernized space suit and even a space telescope have all found friends with deep pockets on the web. Is this the future of science funding? Well, kinda. These projects all have budgets under $10,000. This is far below NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope at almost $9 billion dollars!

Science and technology has found a home in crowdfunding as well. The Pebble Watch, a modernized space suit and even a space telescope have all found friends with deep pockets on the web. Is this the future of science funding? Well, kinda. These projects all have budgets under $10,000. This is far below NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope at almost $9 billion dollars!

Additionally, technology advancements are needed for military and defense, but will the public want to use their own money to fund nuclear weapons? Probably not.

The internet has demonstrated its love for science and willingness to loosen the purse strings for cool projects, so what does this mean for the future? More crowdfunding? Tighter regulation on funding outlets? What about Government and crowdfunding on the same project?

What projects would you pay up for?